Keith joined BSL during his engineering degree, just nine years after our inception. Now, he’s in charge of all things Engineering and Quality within the company.

This week, we sat down with Keith and asked him to tell us a bit about his career in engineering so far:

What inspired you to become an engineer?

I think it was always inevitable that I was going to be an engineer. I was that kid who played with LEGO and Meccano, always building things and taking them apart.

One of my earliest “crimes,” as my mum used to love telling people, was when she bought a brand new bottle of shampoo, and I decided I wanted to know exactly how many squirts were in it. So yeah, I was always leaning towards that kind of thing, always trying to take things apart to see how they worked!

Because of this, all the screwdrivers from the Meccano set ended up getting confiscated because they caught me behind the telly, trying to take the back off. (And this was in the days of big, chunky TVs with tens of thousands of volts running through them) I just wanted to see where all the people were!

Because of this, every time we went to my nan and grandad’s, they had this drawer full of old watches. Proper clockwork ones, with springs and little gears. My entertainment at nan’s was being left with that drawer and a few tiny tools. I’d take the watches apart (could never put them back together) but it kept me quiet for hours!

So I don’t think there was one single moment of inspiration. It wasn’t like I learned about Isambard Kingdom Brunel and just thought, “Right, that’s it, I want to be an engineer.” It was more like… this was just always the path. The only real question was what kind of engineer I’d end up being.

So linking to that: when you first started your education in engineering, did you already have a sense of what kind of engineering you wanted to go into? Or did it take some experimenting to figure it out?

I’d say that probably didn’t happen until about A-levels, when things started to feel more applied.

Obviously, you do have to start specialising a bit as you go along – you can’t keep doing everything. So you naturally end up leaning toward the subjects you enjoy more.

At GCSE, we had to do a language – either French or Spanish – and then history or geography. It was about ticking certain boxes. We also had to do something called triple award science, so biology, chemistry, and physics. You had to do all three, but oddly enough, you only got two certificates for it! And then everyone did English Language and English Literature too.

There were maybe one or two subjects at the end that you could choose freely. I went straight for Design Technology, and I also did Computing. That leaned a little toward the software and programming side of things. Design Tech was what really drew me in.

Then at A-level, you start seriously thinking about where you might want to end up. But it’s still tough as you’re only 16 or 17, and you’re not very informed yet. There are lots of things you enjoy, and narrowing it down can be difficult.

Eventually, you have to build a package of subjects that align with where you’re headed. For me, I didn’t like maths, and never really have. But you need it for engineering. I’ve never been that great at it, to be honest. During my degree, I was basically just buying more and more powerful calculators to get by!

So I focused on maths, physics, and Design Tech again at A-level.

During study periods, I remember spending entire lessons just flipping through the RS catalogue. Back then, it was this giant set of books – four volumes in a cardboard sleeve. I’d just sit there reading it until home time. That’s when I really started leaning more and more toward engineering.

So how long have you been at BSL, and what was your original role?

My first involvement was during university, on a work experience placement in 1999. I was on a four-year taught Master of Engineering course. Traditionally, you’d do a BEng first and return for a master’s, but I applied for the bachelor’s because honestly, I wasn’t confident about my A-levels. I was pretty grumpy about it at the time.

At my school, if you were in sixth form, you applied to university. So I applied to the University of Greenwich. They said, “If you get 18 points instead of 14, we’ll bump you to the MEng course.” I didn’t think I’d get those points… but I did! So I ended up on the four-year master’s track.

Part of that was the six-month industrial placement, which was the second half of the third year. When it came time to choose a company, my tutor said: “There’s a little company near the airport, a guy named Graham. Give him a call.” And that was it.

Back then, we were a tiny team. We just had a small office and test area. So I did the six-month placement, came back during holidays, and then after I graduated they offered me a full-time role. I guess it was a six-month job interview, in hindsight!

Graham was probably thinking about succession planning already. In a small company, you have to think ahead when someone with lots of knowledge might eventually retire. So that’s how I started – doing a lot of the early 3D CAD work, while Julian and I worked together on product development. Some of our current products still trace back to that time.

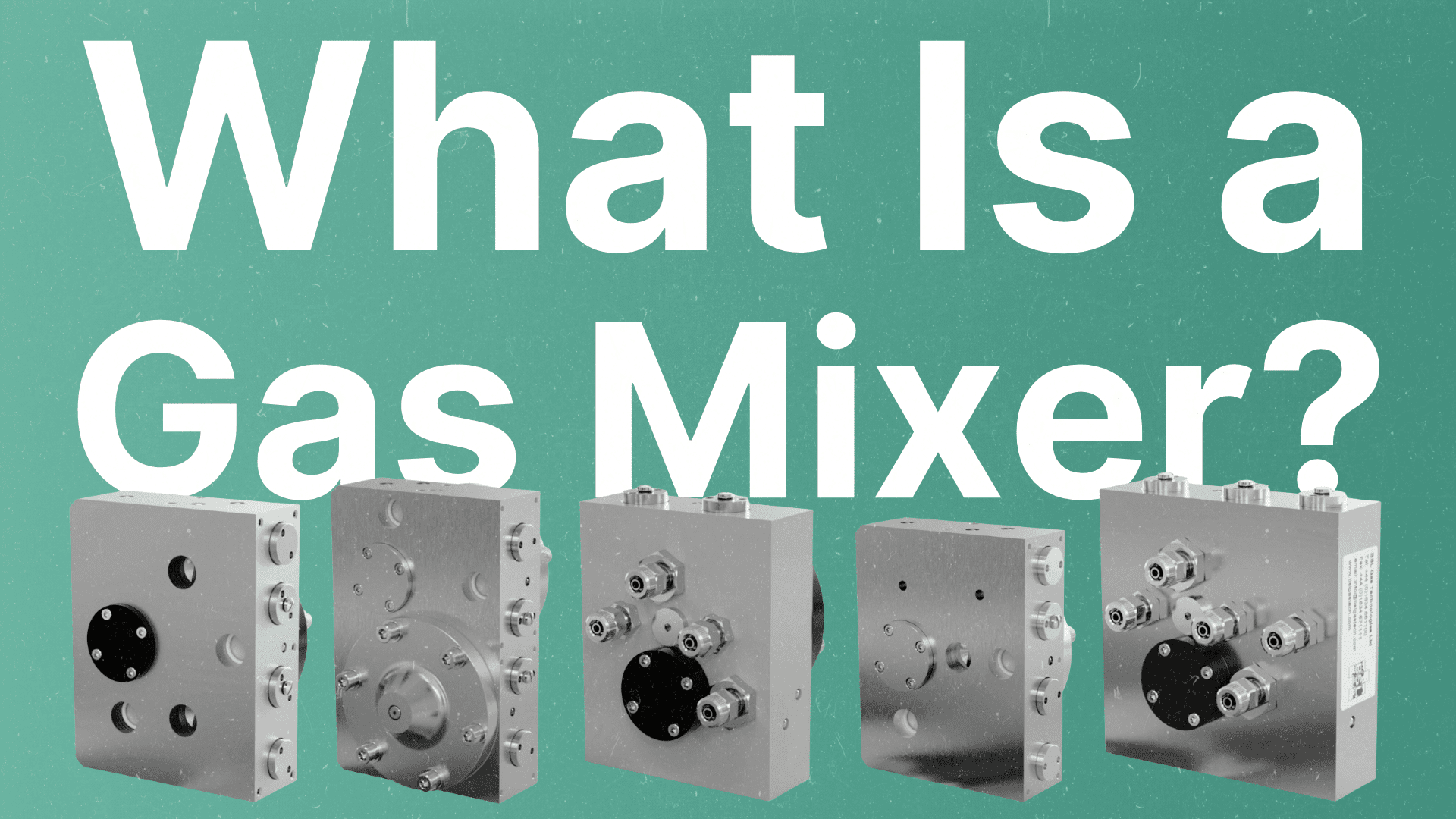

Like the gas mixers?

Yeah, the first adjustable gas mixer – that was me and Julian! The very first version used a blank CD as the adjustment scale and a paper plate with a slit cut into it to view the markings. That was our prototype! The company used to provide lunch every day, so we had plenty of paper plates lying around.

What programs do you use in your work, and which ones do you enjoy the most?

SOLIDWORKS is my baby.

We’ve had SOLIDWORKS CAD software since 2001, and I actually taught myself how to use it.

As part of my degree in 1999, I had to do a six-month placement in industry, and I ended up here at BSL!

At the time, the workload wasn’t too heavy, so I had time to really learn SOLIDWORKS. Many engineers at the time were used to traditional methods. There was still a drawing board in use when I arrived! We would sit at these boards, like architects, drawing everything by hand on A1 sheets.

Meanwhile, I was there campaigning for 3D CAD because I’d seen what it could do at university. Some of the projects we were doing were incredibly hard to visualise in 2D – we genuinely couldn’t have completed some of them without SOLIDWORKS.

At first, the consensus was, “Only new designs will be done in SOLIDWORKS. It’s not going to become a crutch for the whole company. We’ll still do traditional 2D drawings.” But that didn’t last long.

I bet you’re pretty glad you pushed for it!

Oh yeah. Before SOLIDWORKS, we’d hand-draw the design, then send it out to a contractor to digitise in AutoCAD. Drawings would go back and forth – mistakes, corrections – it could take weeks just to issue one.

We even had to use “drawing transmittal forms” to track the handovers. Now, of course, it’s all done in-house, which is faster and far more accurate.

That said, we still maintain some 2D drawings for legacy products. A lot of what we make today has roots in stuff from years ago. But new starters like Tom haven’t even used 2D software before – it’s a generational shift. Even now, relying on 2D drawings feels a bit outdated.

Beyond that, I get involved with Sage, our accounting software, and the website. Whenever anything breaks, I’m usually the one fixing it. Not because I particularly want to be, but because I can. I’ve always leaned toward software – whether it’s parts, assemblies, drawings, rendering, or visualisation, that’s my comfort zone!

What’s the most exciting part of your work at BSL?

For me, it’s the thrill of creating something – seeing a concept go from a sketch or 3D model to a real physical thing. Even more so if it works!

It’s amazing, honestly. You design it, send it off to a machine shop – sometimes in another country – and a few days later, it arrives. And if it actually functions the way you intended? That’s the magic. Especially if it works on the first try. You measure your success by how often that happens.

What future engineering innovation are you most excited about?

That’s the trouble – if I told you, we couldn’t publish this article! Some of the exciting developments and innovations we’re exploring at BSL are confidential, but I can talk around them a bit.

What really drives innovation for us is the stuff we have to say no to right now. If a customer comes to us and we can’t help them – because we don’t have the right product or capability – that’s what sparks ideas for future development. Part of being a good engineer is actually knowing when not to say yes. Knowing when and how to say no is a real skill.

That kind of thinking: where the market is going, what we’re saying no to, and what we could do. That’s what shapes the future of our engineering.

What advice would you give your younger self stepping into this role?

Possibly just… be braver. Especially with travel. I used to avoid it at all costs, found it incredibly stressful. But looking back, those trips were the most memorable.

We once did a trip to China. We were travelling city to city – Nanjing, Shanghai, Pudong to visit gas companies with our translator, Charlie Dang. Every presentation would fall apart at the same point, and I thought it was me. Until the third day, Charlie admitted, “I don’t understand how the bias relay works.” That was the part he couldn’t translate – and that’s where everything kept breaking down. Once we sorted it, the final presentation went much better.

It was incredibly stressful at the time, but now? It’s a story.

You must have done quite a bit of travelling by now then!

Yeah – China, Poland, Czech Republic, America. One of the most memorable was a road trip from Portland, Oregon to Montana. We did an exhibition, then drove to Montana. It was amazing – proper American freeways, coal trains, all of it.

Every hotel I stayed in had a broken toilet. One motel had a rope looped around the door handle as its only lock. The room was next to a railway crossing, and massive coal trains went by every 15 minutes, horns blaring through the night. We didn’t sleep a wink. But again – unforgettable.

So what’s the most important piece of advice you’d give to someone wanting to become an engineer?

Academically, you need maths, physics, design tech – computing helps too. You need the right subjects to get on the degree course. But beyond that, I’d say: show your passion.

If someone came to me with examples of personal projects – like building a plant-watering system or designing models with a 3D printer – I’d be more interested in that than a polished CV. Especially at BSL, we need people who can finish things: build prototypes, test them, refine them.

You do need a baseline in maths, but if it’s not your strength, you can get by with a decent calculator! A lot of what you learn in school won’t directly apply. There’s no degree for building gas blenders. Some of this stuff is just… dark lore and tinkering.

And when it comes to exams, there’s a real skill to passing them. Learn to spot what might come up. Start with high-mark questions you can answer well. That’s how I got through A-levels!

If you could swap roles with anyone on the team for a day, would you?

Julian said he wouldn’t because he likes his job too much – and honestly, I feel the same. I dip in and out of other areas already, so I get glimpses into what other people are doing. But I wouldn’t want to be in those roles full-time. I like my job that much.

This is just what I do. It’s what I’ve always been meant to do.

What’s your proudest moment at BSL?

There’s one I can’t really talk about! Let’s just say it involves a very special customer and a very specialised product. It’s our biggest project to date, in terms of complexity and importance.

What I can say is that getting that first order – for that very custom, high-spec product – felt like a real milestone. It was the kind of engineering that matters, and I’m incredibly proud of it.

If you weren’t an engineer, what would you be doing?

When I was younger, I wanted to be a pilot. I even looked into joining the RAF – but they’re quite fussy about eyesight, and I’ve worn glasses since I was six!

Then, believe it or not, I thought about becoming a driving instructor. Mine always seemed really content: just driving around, chatting, picking his own hours. He even taught me how to use a petrol pump, which most instructors skip. It’s a small thing, but it really helped. That, or maybe I’d just be tinkering with things full-time!

Is there an engineer or inventor you look up to?

He actually went to my school, and the A-Level Physics lab was named after him. He was a mathematician by background, but he worked on the supercharger for the Rolls-Royce Merlin engine (the one used in Spitfires) and also the Rolls-Royce Pegasus, which powered the Harrier jump jet.

One of the school trophies was a scale model of a jet engine. That sort of thing definitely left an impression.

Do you have any hobbies outside work, and do they relate to engineering?

Analogue film cameras are fascinating. Especially the later ones from the ’70s and early ’80s – just before everything went digital. Those were really the pinnacle of what you could do with mechanical engineering at a small scale. Springs, levers, balancing mechanisms – all packed into a sensibly sized camera body. They’re amazing bits of kit!

I’ve also got a 3D printer at home, which I suspect most engineers do. But rather than printing Yoda heads or Star Wars helmets (looking at you, Tom), mine usually prints… better parts for itself. That’s the classic engineer mindset: “I could have designed that bracket better.”

My first printer was from a Kickstarter project. It was awful. The design was poor, and support was non-existent – just a few people who thought, “Let’s make a 3D printer and get rich.” So it quickly became a whole community project: users helping each other figure out how to make the thing actually work. It became this self-reinforcing cycle of printing just well enough to print parts that would improve it. It was kind of brilliant in its own broken way.

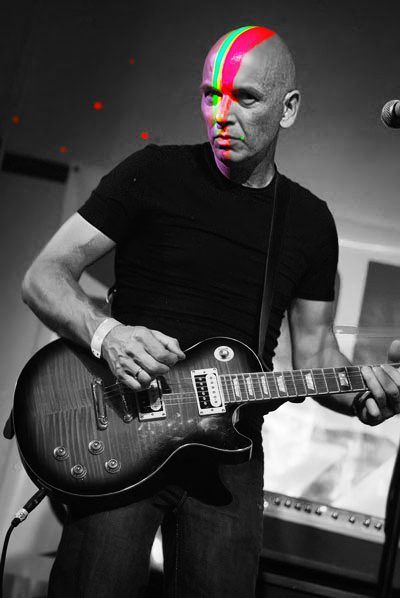

Oh, and as Julian’s probably already told you – we were in a band once!

We used to rehearse on the mezzanine in this building when it was mostly empty. Julian was lead guitar, and I’d always been interested in bass, so I stepped in and learned as I went.

Stay tuned for more exclusive interviews, as we celebrate the brilliant minds behind our gas mixing equipment.

If you’re interested in reading our other blog posts, you can do that here. Make sure you’re following us on LinkedIn, Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and Instagram so that you never miss an update from us.